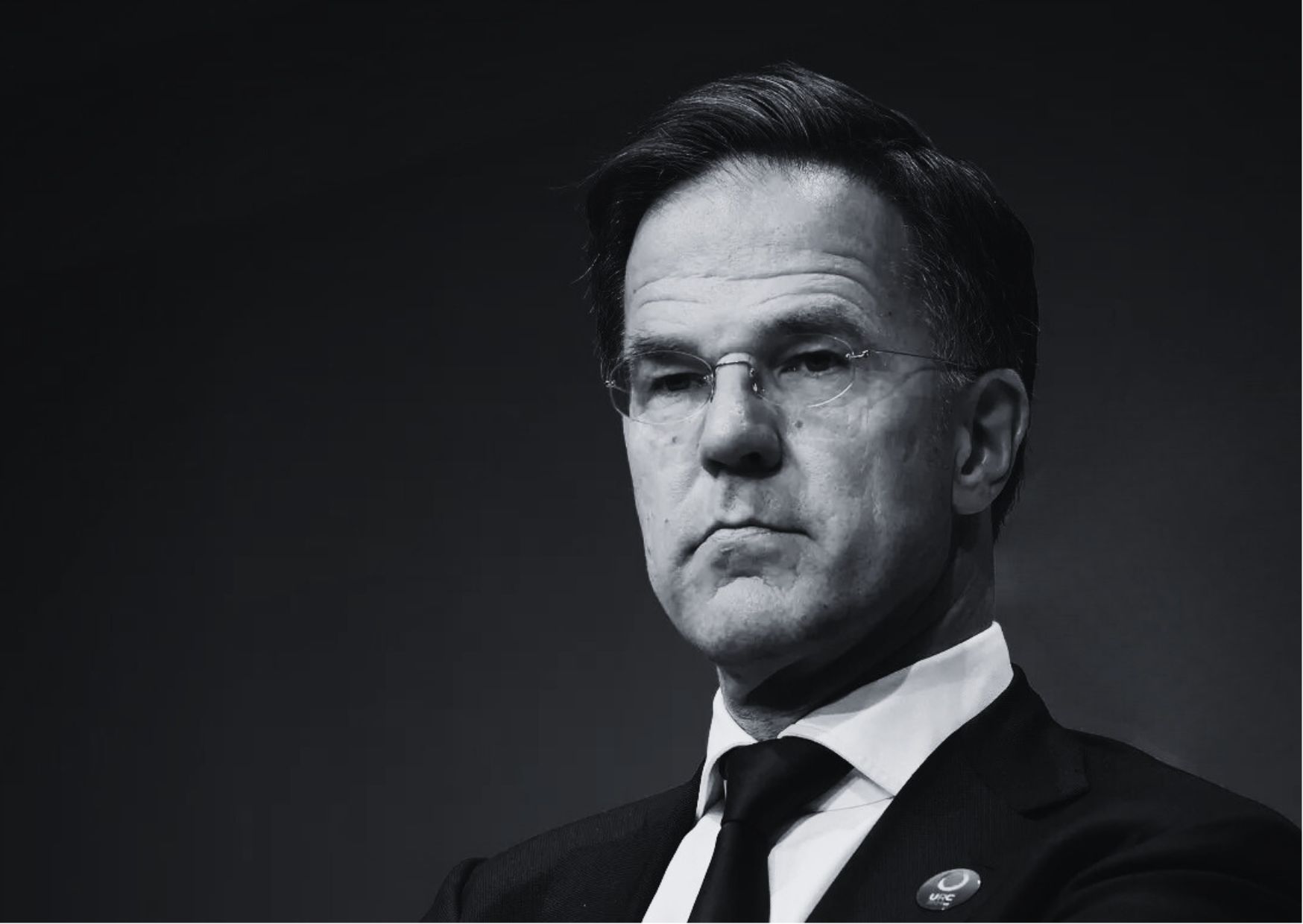

Speaking to The New York Times, Rutte outlined a scenario in which Beijing, prior to launching a military campaign in the Indo-Pacific, could encourage Moscow to create a diversion in Europe by escalating its aggression against the West.

“Let’s not be naive,” Rutte said. “If Xi Jinping would attack Taiwan, he would first make sure that he makes a call to his very junior partner in all of this, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, and tell him: ‘Hey, I’m going to do this, and I need you to keep them busy in Europe by attacking NATO territory.'”

The statement reflects growing concern in NATO capitals over the strategic alignment between Russia and China, particularly since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Rutte suggested this dynamic could represent a template for China, which continues to signal interest in regaining control over Taiwan.

Ukrainian intelligence has also drawn attention to increasing Chinese involvement in Russia’s war effort. On 6 July, Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence reported that 65% of the components found in Iranian-designed Shahed drones used by Russia were manufactured in China and labelled with Chinese branding. The real figure may be higher when accounting for Western components rerouted through China.

These findings support the wider assessment that China is enabling Russia’s military-industrial complex through indirect supply chains and dual-use technologies. While Beijing avoids overt arms transfers to evade formal sanctions, it has systematically expanded its economic and technological support to Russia since 2022.

Rutte warned that Russia, bolstered by this support, could rebuild its military capabilities within five years to a level that would once again pose a conventional threat to NATO territory. He called for greater urgency in strengthening NATO’s deterrent posture and closer cooperation with partners in the Indo-Pacific region. “To deter them,” he added, “we need to do two things. One is that NATO collectively must be so strong that the Russians will never do this. And second, we must work together with the Indo-Pacific.”

This warning coincides with strategic reassessments taking place in the United States and Europe amid signs that China is preparing for a wider confrontation with the West. Analysts note that Russia’s wartime economy has been restructured to serve both its military needs and China’s long-term geopolitical interests. Moscow’s dependence on Beijing is growing across financial, technological, and energy domains.

According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, Russia’s defence spending in 2024 rose by 42% in real terms, reaching $462 billion and exceeding the combined military expenditure of all European NATO members.

Observers point out that the Kremlin’s political system, now heavily influenced by Beijing, has become structurally dependent on continuous warfare. A further escalation after Ukraine would align with Moscow’s expansionist ideology and China’s objective to confront the US-led security architecture.

Some experts argue that China is pursuing a dual strategy: maintaining economic partnerships with Western states while undermining them strategically through alliances with Russia, North Korea, and Iran. Reports from recent diplomatic meetings, including a closed-door exchange between Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and EU High Representative Kaja Kallas, suggest that Beijing has no intention of allowing Russia to lose the war in Ukraine.

India’s role in this context is increasingly viewed as pivotal. As the world’s most populous democracy with a large industrial base, New Delhi is courted by both Western powers and BRICS states. However, despite India’s continued energy trade with Russia, its strategic posture remains firmly non-aligned, with deepening defence cooperation with Japan, Australia, and the United States. India’s participation in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and other regional frameworks is regarded as essential to balancing Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific.

Meanwhile, internal divisions within BRICS could limit the bloc’s potential to act as a unified anti-Western alliance. Recent summits have shown divergent interests between China and member states such as India and Brazil. The absence of Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin from the latest BRICS opening ceremony has been interpreted by some as a signal of disunity.

China’s broader ambitions to reshape the international order remain clear. While its economic position is challenged by slowing growth, supply chain diversification, and diminishing access to Western markets, Beijing continues to exploit geopolitical instability to secure influence.

Rutte’s warning may therefore be read not only as a theoretical assessment but as a call for Western nations to take more seriously the interconnected nature of threats in Europe and Asia. With Russia acting increasingly as a proxy of Chinese strategic interests, any future confrontation over Taiwan could bring with it the risk of escalation on NATO’s eastern flank.