Europe, it seemed, had other priorities: climate ambitions, social welfare, diplomatic fatigue, and the belief that security would always be outsourced across the Atlantic. Then came 2022. Russia’s grotesque invasion of Ukraine shattered our illusions. Today, the latest NATO Defence Expenditure Report doesn’t merely chronicle rising budgets—it nods to a new era of continental resolve. Europe is not just paying lip service; it is rearming.

The report quietly, but tellingly, confirms what we already suspected: as of 2025, every NATO member has met the Alliance’s longstanding—but often unmet—2% of GDP defence target. Once, fewer than a dozen did; now, all 32 stand shoulder-to-shoulder behind the benchmark. And yet, Brussels isn’t resting on that modest accomplishment.

At the June 2025 Hague Summit, leaders agreed to aim even higher—a future where 5% of GDP annually is devoted to “core defence and security”, broken down into 3.5% for traditional military readiness and 1.5% for security-related resilience. That is no modest ambition; it’s a statement welcome enough to make America’s jaw drop.

Only three nations—Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia—currently meet the elevated 3.5% threshold, with Poland setting the example at around 4.5%. Yet the commitment, if realised, would dramatically reshape NATO’s industrial and operational landscape.

It would be tempting, at a glance, to dismiss all this as mere political theatre: ministers posing with statements, summit selfies, ceremonial declarations. But for once, the contours of intention match the rhetoric.

Rheinmetall’s ammunition factory in Lower Saxony is a vivid sign of this shift. A newly inaugurated €500 million plant, already slated to produce 350,000 shells annually by 2027, anchors Germany’s readiness not just to spend, but to supply. Few symbols could speak louder to the Alliance’s newfound seriousness.

Let us be clear: meeting these defence spending targets won’t be painless—especially for countries already running fragile budgets. The Janes analysis warns starkly: moving from 2% to 3.5% of GDP across NATO alone implies an additional $1.4 trillion annually by 2035. And if you stretch to 5%? The cumulative figure balloons to around $4.2 trillion.

Yet the alternative is a Europe unprepared for the threats that stalk us. If Putin or his successors choose to threaten land borders, freeze energy supplies, or sabotages cables, the cost of being unarmed will be devastatingly higher.

Critics argue that such spending will cannibalise social and environmental investment. The New Economics Foundation, among others, warns of a trade-off: record military budgets risk hollowing out climate programmes and welfare systems.

Taken in isolation, that’s a legitimate concern. But the broader truth is that defence and resilience are increasingly non-negotiable. Social welfare flourishes only under conditions of peace. If Europe cannot defend its borders, no amount of social spending will save democracy.

Forecasting trillions is one thing; turning budgets into real operational capacity is another.

The report—and its surrounding analysis—clearly identifies the need for radical reform of defence procurement and industrial collaboration. National ministries and allied firms must do better, faster, more strategically. NATO’s own Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA) offers one path forward: a network of testing hubs and accelerators that injects commercial agility into defence innovation.

We must not revert to old mistakes: dispatching money to grand defence agencies without ensuring the goods get made, delivered, and integrated.

Meeting 5% of GDP requires not just money, but continuity—consensus between political cycles. One noteworthy thread through the report is how Eastern and Northern European states—especially the Baltics and Poland—are paving the way.

These are countries that, sadly, needed few reminders of strategic peril. They pressed the case for urgent rearmament when others were still debating.

Germany and France, often sluggish on defence reform, must now catch up—or cede leadership. Britain, too, with its own trouble juggling aid and arms, will need to recalibrate in a world demanding clarity, not convenience.

There were criticisms in the run-up to the summits: will governments meet these defence targets by merely repackaging infrastructure work—ports, energy grids—as “security related”? The inclusion of non-military infrastructure in the 1.5% of GDP requires vigilance. Spain, for instance, has drawn strain for opting out and claiming no military gap despite underspending.

The Ankara Summit’s follow-up is scheduled for 2029. That will be the moment when hollow commitments face reality: are more roads in Spain going to deter enemy tanks? Or are they a sop to political convenience?

In a world that prefers avoiding inconvenient truths, the NATO 2025 report reads like a wake-up call.

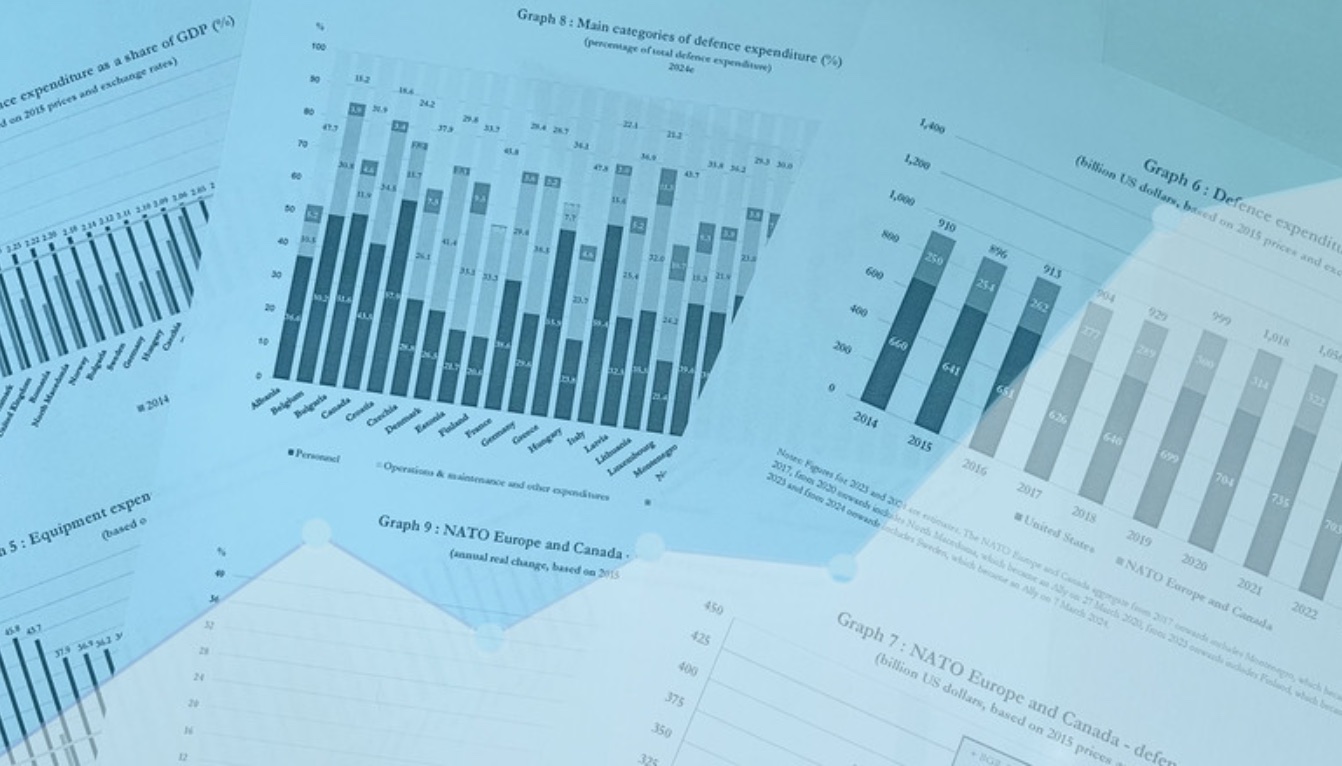

NATO nations have moved past simply hitting 2% of GDP defence spending. All 32 now meet that benchmark.

Leaders envisage not 2%, but 5% of GDP by 2035—3.5% for core defence, 1.5% for resilience and infrastructure.

Very few currently meet the 3.5% bar—Poland, Lithuania, Latvia. But the framework is in place.

Germany’s Rheinmetall plant, producing hundreds of thousands of artillery shells, illustrates defence is more natural now.

Yet the spending will be politically and logistically complex. Delivering capabilities—not just numbers—will define success or failure. DIANA, acquisition reform, and smart budgeting matter.

Europe has rediscovered its capacity to act, to invest, and to fear. In the age of tanks, cyber, and uncertainty, it cannot afford hesitation—or illusion. What remains essential is turning resolution into readiness. The next test won’t be a summit; it will be in the factories, training grounds, and invoice books where security is built—not bellowed.

Main Image: NATO Newsroom

___________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________