They went under NATO banners, UN mandates, or national expeditions, serving governments that insisted such missions were necessary to confront terrorism, stabilise fragile states, and defend Western values.

Yet for many of those who served, the true reckoning has come not on the battlefield but long after returning home. Instead of gratitude, they have found themselves ensnared in inquiries, legal proceedings, or public scepticism about the wars themselves. In Britain, veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan have faced protracted investigations into battlefield conduct.

In Northern Ireland, former soldiers who served at the height of sectarian violence have been dragged back into court decades later. Across the continent, French, Dutch, German and Italian veterans of foreign campaigns voice a quieter but equally corrosive doubt: was it worth it?

The result is a spreading disillusionment. Europe’s veterans often feel abandoned by the very states that sent them into harm’s way, left to shoulder moral burdens that politicians, diplomats and public opinion now shirk.

No country illustrates the dilemma more starkly than Britain. The Iraq and Afghanistan wars still cast a long shadow, with thousands of soldiers compelled to give evidence before endless inquiries. The Chilcot Report, sprawling and inconclusive, blamed politicians but left many service personnel feeling as if the true accountability had been shuffled downwards. Special forces units who operated in Helmand now face reopened investigations into actions taken in split-second firefights. For men who believed they were defending their country, the prospect of a knock on the door years later is a source of constant dread.

But it is Northern Ireland that has become the most poisonous theatre of all. Decades after the Troubles, ageing veterans in their sixties and seventies are still being hauled before courts for decisions made in what were, by any measure, chaotic and life-threatening circumstances. The Northern Ireland Legacy Act, which came into effect in 2023, was meant to draw a line under this. It offered immunity from prosecution in exchange for co-operation with truth recovery efforts, and the Government loudly proclaimed it would protect soldiers who had already endured a lifetime of legal uncertainty.

Yet the Act has satisfied no one. Victims’ groups condemn it as a denial of justice. Veterans argue it offers no real protection, since cases already under way can still drag on and the door remains ajar for future challenges under human rights law. The result is a half-solution that pleases neither side, leaving former soldiers exposed to the grinding machinery of the courts while politicians wash their hands of responsibility.

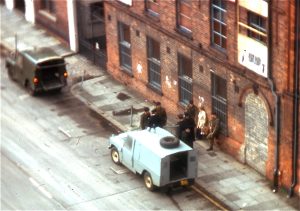

The bitter irony is not lost on those who served. These men were once deployed to Northern Ireland by the British state to keep order when the police could not. They lived under constant threat, operating in a grey zone where civilians could be combatants and every street corner concealed a bomb or a gunman. Now, half a century later, some find themselves treated less as defenders of the realm than as suspects in a criminal dock.

For veterans of Iraq, Afghanistan and Ulster alike, the message seems clear: Westminster will send you abroad, or even onto the streets of Belfast, but it may not stand by you when the political winds change. That sense of betrayal is corrosive, and it explains why many young soldiers now wonder whether the duty of loyalty still runs both ways.

The unease is not confined to Britain. In France, veterans of interventions in Mali and the wider Sahel increasingly question whether their sacrifices were squandered. The mission to stabilise the region against jihadist groups was once hailed as a model of decisive European action. Yet French forces withdrew under pressure from hostile governments, leaving much of the territory once again vulnerable to Islamist insurgents. Soldiers who lost comrades now watch local leaders welcome Russian mercenaries into the same towns they once patrolled.

German veterans of Afghanistan face a similar reckoning. Berlin deployed more than 90,000 troops to the mission over two decades, with 59 killed and hundreds wounded. When Kabul fell in 2021, many veterans spoke openly of betrayal: they had fought, sacrificed, and yet watched the mission collapse in days. Now, years later, some continue to face official questioning about civilian casualties in Kunduz and other hotspots, with prosecutors examining whether rules of engagement were breached.

The Dutch still wrestle with the legacy of Srebrenica in the 1990s, when UN peacekeepers failed to prevent the massacre of more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys. Though the context was chaotic and the mandate limited, veterans have endured decades of public debate about whether they were scapegoated for political and diplomatic failures.

For many veterans, the deepest wound is not legal scrutiny but moral uncertainty. They served loyally, often believing they were contributing to a safer world. Years later, they see Iraq ravaged by sectarian violence, Afghanistan returned to Taliban control, Mali destabilised, and Libya fragmented. The promises that politicians made – of democracy, stability, reconstruction – have rarely been fulfilled.

This disillusionment eats away at morale. Soldiers are trained to accept risk, even to give their lives. What they cannot accept is the sense that their sacrifices were futile, or worse, cynically used for political ends. Veterans’ groups across Europe report rising levels of depression linked not only to trauma but to existential doubt. The haunting question is not just “what did I see?” but “what was it for?”

Compounding the problem is Europe’s wider public mood. Unlike in the United States, where veterans are often accorded a special status in civic life, many European societies remain ambivalent. In Germany, historical sensitivities make open celebration of the military awkward. In Britain, the Armed Forces still command respect, but fatigue from Iraq and Afghanistan has left many civilians reluctant to hear about those conflicts. In France, public attention has shifted rapidly from the Sahel to domestic issues.

Veterans thus feel doubly abandoned: legally vulnerable and socially invisible. The charities and associations that support them do valiant work, but political leaders rarely champion their cause. Promises of reform – from stronger legal protections to better pensions – are made and quietly shelved.

The burden carried by Europe’s veterans is not only a humanitarian concern; it is a strategic one. If younger soldiers conclude that service abroad leads to prosecution at home, recruitment and retention will inevitably suffer. Who will volunteer for difficult missions in unstable regions if they believe that in twenty years they may be standing trial?

Already there are signs of reluctance. Some European militaries struggle to fill their ranks, even as NATO demands greater readiness in response to Russia’s aggression. The shadow of past missions looms large: politicians promise solidarity with Ukraine and deterrence against Moscow, but veterans’ experiences whisper a warning that words of gratitude may fade into court summonses and broken promises.

Europe faces a difficult balance. Upholding the rule of law and investigating genuine abuses is essential; no democracy can tolerate impunity. But there is a difference between accountability and persecution, between fair scrutiny and endless legal jeopardy. Veterans need certainty, not the prospect of cases being reopened decades later.

More broadly, Europe must reckon with the morality of its interventions. If foreign missions are launched with fanfare and moral purpose, leaders owe it to the men and women they send to ensure that purpose is sustained – not abandoned once domestic politics move on. Otherwise, the cycle of disillusionment will deepen, corroding the very foundations of military service.

The legal and moral burdens borne by Europe’s veterans are a symptom of a deeper malaise: a continent that asks much of its soldiers but struggles to stand by them when the battles are over. From Belfast to Kabul, Gao to Sarajevo, Europe’s warriors are haunted not only by the memories of combat but by the uneasy knowledge that their sacrifices may be forgotten, questioned, or even punished.

Unless governments confront this reality – with clearer legal protections, honest political leadership, and genuine recognition – they risk creating a generation of embittered veterans and a future force reluctant to serve. The men and women who carried Europe’s flag abroad deserve more than inquiries and indifference. They deserve the certainty that their duty will not one day become their downfall.

Main Image: UK – Defence Images

_____________________________________________________________________________

In a thunderous rebuke to official silence, Britain’s most elite warriors — the SAS, SBS and SRR — have broken cover in an unprecedented show of unity, demanding an end to what they call a legal “witch-hunt” against veterans of the Northern Ireland conflict.

For decades, these shadowy professionals operated in silence and secrecy. But now, driven by what they see as betrayal from the political class, their voices are being raised in anger and in unison.

_____________________________________________________________________________