The decision by Australia’s Electro Optic Systems (EOS) to pivot decisively towards Europe should be read not merely as a commercial story, but as a warning: those who hesitate will miss the moment.

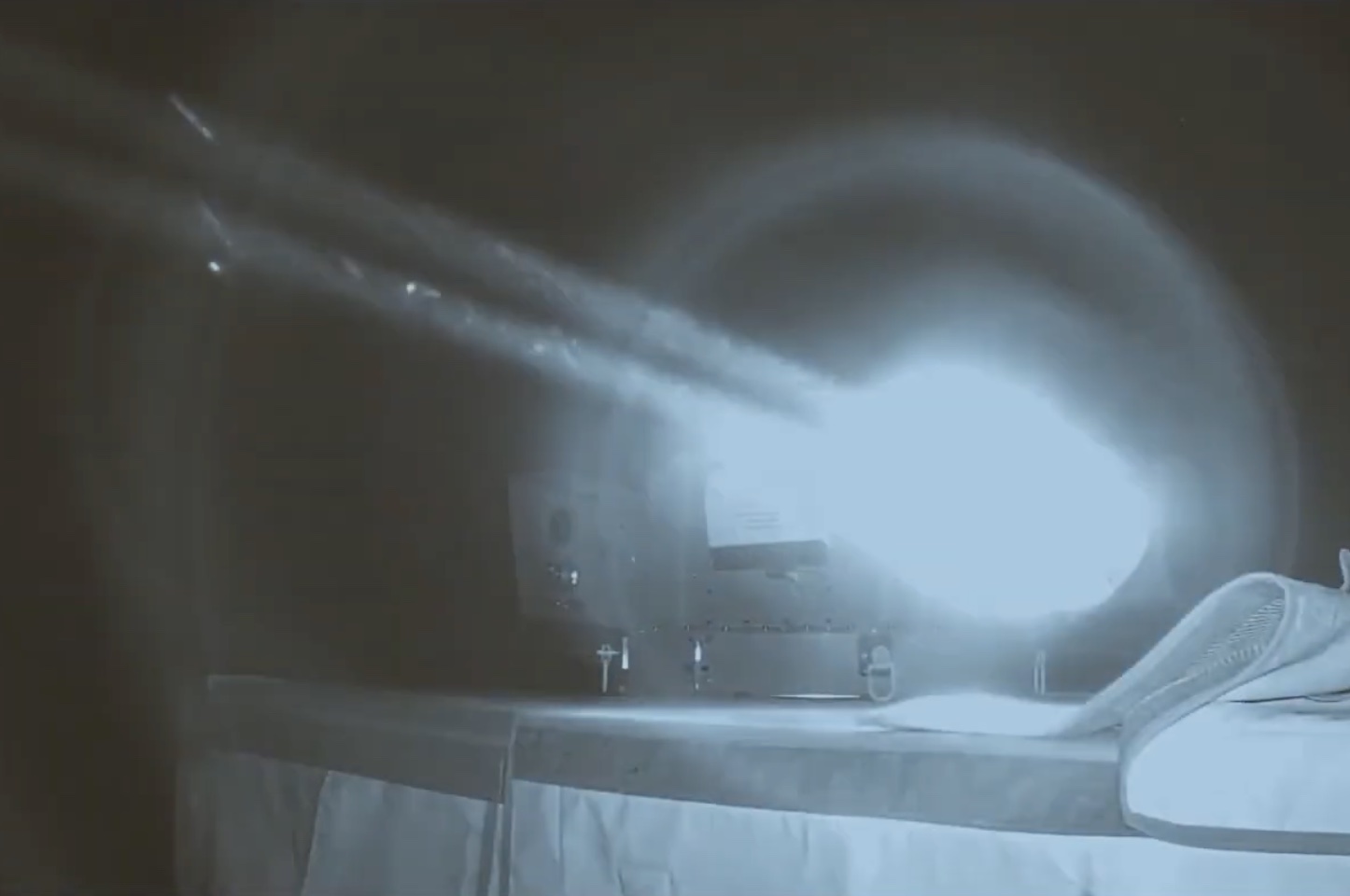

EOS, a relatively little-known Australian firm, has quietly become one of the world’s leaders in high-energy laser systems designed to counter drones and other aerial threats. Its €71 million contract with the Netherlands last year — the first export sale globally of a 100-kilowatt-class laser weapon — marked a decisive leap from laboratory promise to operational reality. While Europe debates frameworks and funding instruments, others are already delivering innovative on-target solutions.

The company’s chief executive, Andreas Schwer, has now made clear that Europe is not just a market but the future centre of gravity for EOS. A relocation of headquarters from Australia to Europe, alongside a potential relisting on a European exchange, is under serious consideration. Germany and the Netherlands are leading contenders. The message is unmistakable: Europe’s defence demand is booming — but only for those able to act at speed.

That urgency is driven by the brutal arithmetic of modern warfare. Ukraine has demonstrated beyond doubt that cheap drones can exhaust even the most sophisticated air defence systems. Firing missiles costing hundreds of thousands of euros to destroy drones worth a few thousand is a losing proposition. Laser weapons promise something radically different: near-instant engagement at negligible marginal cost. Once the system is powered, each shot costs little more than electricity.

Yet despite years of discussion, Europe remains dangerously behind in deploying high-energy lasers above 50 kW at scale. While the United States, China and Israel have pushed ahead — Israel’s Iron Beam system is already operational in limited roles — most European programmes remain stuck in demonstrator mode. That gap matters. In a conflict defined by saturation attacks, prototypes do not stop drones.

EOS’s appeal lies not just in the technology itself but in its readiness. The company controls its intellectual property and can deliver exportable systems now, not in the next decade. This is particularly significant as American laser systems above 50 kW are likely to face stringent export restrictions. If Europe wants operational autonomy rather than dependency, it cannot rely indefinitely on Washington’s permission slips.

There is also a strategic subtlety at play. Directed-energy weapons change battlefield dynamics in ways that suit European forces. Laser engagements are silent, invisible and instantaneous. There is no missile plume, no radar cue, no warning to the attacker. Against swarming drones — increasingly autonomous and expendable — this matters. Lasers do not merely defend; they deter by making attacks economically futile.

To be clear, laser weapons are not a silver bullet. Their effectiveness can be degraded by fog, rain or dust, and their power and cooling requirements complicate deployment. But these are engineering challenges, not conceptual ones. The trajectory is obvious. Systems will become more compact, more powerful and more resilient. The only real question is who deploys them first.

Europe’s risk is not technological ignorance but institutional delay. Defence procurement remains fragmented, ponderous and politically risk-averse. While national programmes inch forward, companies like EOS are offering something Europe rarely produces itself: an off-the-shelf capability with a clear upgrade path. If European governments hesitate too long, they may find that the industrial ecosystem relocates elsewhere — taking expertise, jobs and strategic leverage with it.

EOS’s recent acquisition of MARSS, a European command-and-control specialist, reinforces this point. Modern counter-drone warfare is not about a single weapon, but about integration: sensors, AI-driven decision-making and rapid effectors working as one system. Europe has many of these components — but too rarely combines them at speed.

The lesson should be obvious. Europe can either treat laser defence as another slow-burn collaborative project, or it can act with the urgency the strategic environment demands. The threats are real, the technology is ready, and the industrial partners are waiting.

If Europe truly believes that the age of massed drones and cheap precision attack has arrived, then delay is not prudence. It is exposure.

Starlink terminals on Russian drones raise fears of real-time targeting