Recognition, because Starmer has shown us time and again that he is either unwilling or unable to grasp the realities of power, ideology and national interest.

This was not diplomacy. It was naïveté dressed up as statesmanship.

China is not simply another trading partner with a different political system. It is a one-party, godless Communist state that systematically persecutes religious believers, crushes dissent, erases minorities and surveils its own people with industrial efficiency. To walk into that environment without confronting it directly is not pragmatism. It is abdication.

Starmer spoke warmly of “dialogue” and “co-operation”. What he did not speak about — at least not with any conviction — were the underground churches raided at dawn, the pastors imprisoned for preaching, the Muslim Uyghurs herded into camps, the Buddhists monitored, the Falun Gong erased from public life, or the simple fact that belief itself is treated by the Chinese Communist Party as a rival ideology to be crushed.

China is hostile not merely to Christianity, Islam or Buddhism, but to the very idea that allegiance might lie anywhere other than with the Party. That is why religion is persecuted. That is why faith leaders disappear. That is why crosses are torn down and mosques “sinicised”. To pretend otherwise is to participate in a lie.

Yet Starmer, a man who never misses an opportunity to lecture Britons on values, suddenly finds his voice fails him when faced with a regime that imprisons priests and bulldozes conscience.

This selective morality is becoming his hallmark.

Worse still is his continued enthusiasm for China’s proposed “super embassy” in London — a project so vast, so strategically questionable, that it has alarmed not only residents and local councils, but British intelligence agencies themselves. MI5 and MI6 have reportedly advised against it. So have allied governments. Yet Starmer presses on regardless, as though the security services were merely another interest group to be overruled.

One has to ask: why?

Why is a Prime Minister so dismissive of the advice of his own intelligence agencies when it comes to a hostile authoritarian power? Why is he so relaxed about granting Beijing an unprecedented physical footprint in the heart of London? And why does he seem so eager to accommodate a state whose strategic objectives are increasingly at odds with those of Britain and its allies?

Does Keir Starmer know who this country’s allies are? Does he know who its potential enemies are?

It would appear not.

The United States, Australia, Japan and much of Europe have woken up — belatedly, perhaps — to the reality of Chinese power projection. They have tightened security, restricted influence operations and become more forthright about human rights abuses. Britain, under Starmer, seems to be drifting in the opposite direction: softer language, warmer gestures, fewer red lines.

One could forgive this if it were part of a coherent grand strategy. But there is no strategy here — only vibes. The vague hope that engagement will civilise a regime that has spent decades proving that it has no interest in being civilised.

This is not how serious countries behave.

What troubles me most is not that Starmer is wrong — politicians often are — but that he seems genuinely gullible. There is a boy-scout quality to his foreign policy: the belief that if Britain behaves nicely, others will reciprocate. That if we show respect, respect will be returned. That ideology can be smoothed away by process.

China’s rulers do not think this way. They understand power, leverage and weakness. And they are very good at identifying the latter.

At home, Starmer projects managerial competence. Abroad, he looks like a man out of his depth, clinging to the assumptions of a liberal order that no longer exists. His apparent indifference to China’s state-sanctioned abuses is not merely a moral failing; it is a strategic one. When Britain will not speak plainly about persecution, others take note — including those doing the persecuting.

All of this comes at a time when Starmer’s grip on his own party appears increasingly fragile. His dire performance in office, the absence of economic momentum, the hollowing-out of Labour’s traditional base, and his technocratic aloofness have fuelled growing speculation about a leadership challenge in the months ahead.

In that context, questions about loyalty become unavoidable.

I do not mean loyalty in the crude, conspiratorial sense. I mean something more fundamental. Where does Starmer’s instinctive allegiance lie? With the nation he governs, warts and all? Or with a particular worldview — a post-national, managerial ideology that treats sovereignty, borders and alliances as inconveniences to be managed rather than realities to be defended?

Too often, it feels like the latter.

Starmer is far more animated when discussing abstract “international norms” than when defending Britain’s concrete interests. He is more comfortable appeasing foreign autocrats than confronting them. More at ease chastising his own country than challenging regimes that imprison priests and silence entire peoples.

That is not moral seriousness. It is moral confusion.

Britain does not need a Prime Minister who thinks every problem can be solved by a roundtable and a communiqué. It needs leadership that understands that some regimes are adversarial by nature, that ideology matters, and that values are not something you quietly set aside when they become inconvenient.

In the interests of the country, it may well be better to remove Keir Starmer sooner rather than later. Not because he is malevolent, but because he is weak where strength is required, naïve where scepticism is essential, and silent where clarity is demanded.

A Prime Minister who cannot bring himself to confront China’s abuses, who ignores his own intelligence agencies, and who seems uncertain about who Britain should stand with in an increasingly dangerous world, is not a Prime Minister Britain can afford.

History is rarely kind to leaders who mistake politeness for prudence. Nor should it ever be.

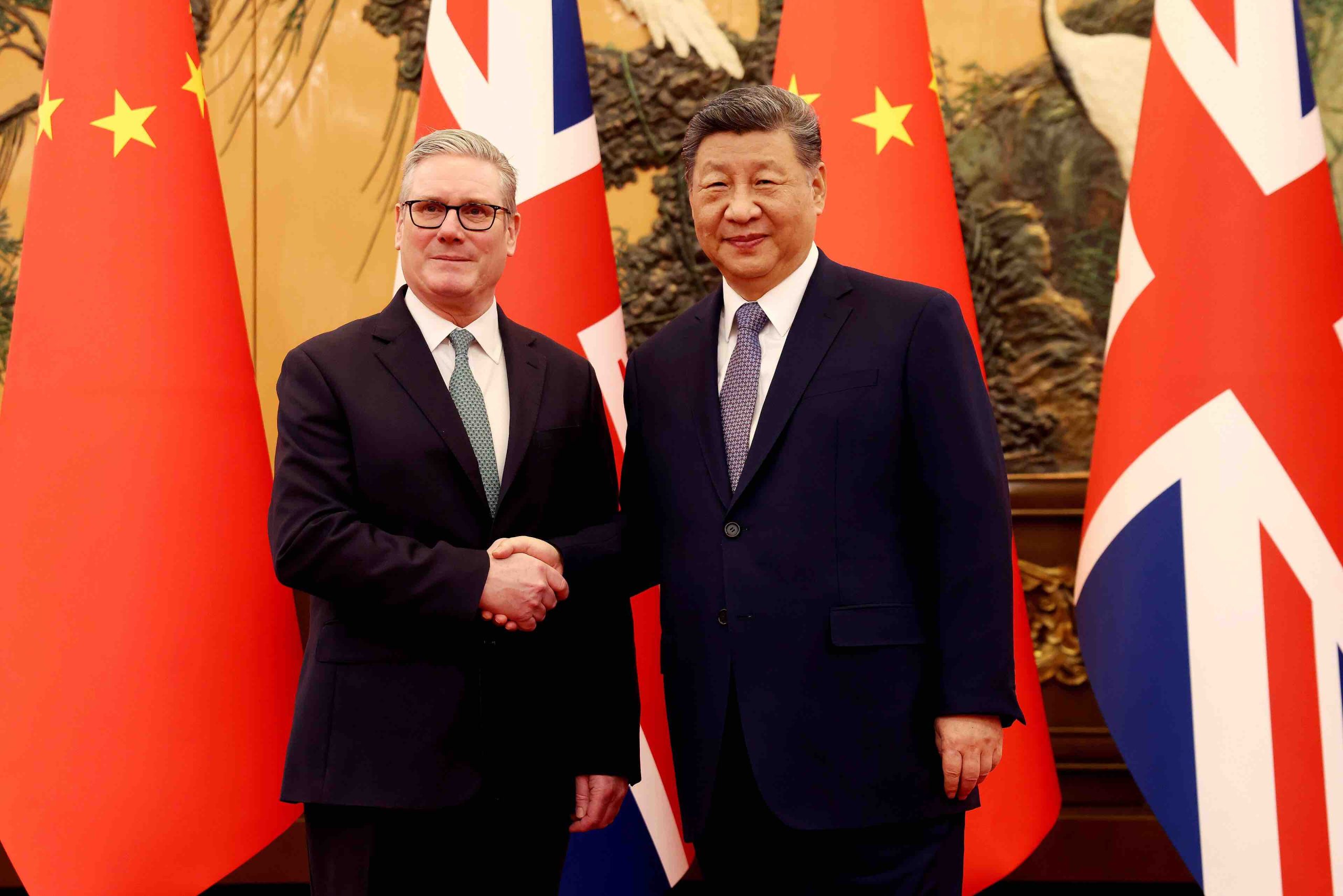

Main Image: By Number 10 – Prime Minister Keir Starmer visits China, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=182657644

If Russia Wins: A Scenario and the Logic of the West’s Managed Defeat